I have recently read the article published in Sociologists Without Borders vol. 8, no.2, 2013 by Chabot and Sharifi, “The Violence of Nonviolence: Problematizing Nonviolent Resistance in Iran and Egypt.” I have serious qualms about the arguments made in the article.

The authors divide the practice of nonviolent resistance into two camps: the Gandhian struggle based on ethical and value-based principles, on the one hand, and the Sharpian nonviolent resistance based … well… on unethical or less ethical principles – an “instrumental” or “political technique”, on the other hand. The authors side, no wonder given their language of absolutes, with the former – I call it – principalist view. And they admonished the latter – pragmatic approach – for promoting “global neoliberal capitalism” that ends up “reproducing various structures and forms of violence.”

I found these arguments counterproductive for the field of civil resistance as well as anti-factual.

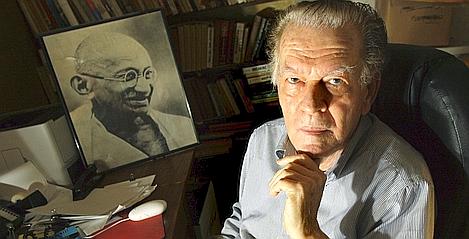

1. The authors ignore entirely the fact that Sharp published his seminal work in the field of nonviolent conflict in 1973 when, in the age of the bipolar world and a nuclear rivalry, civil resistance was hardly recognizable as a force to reckon with not to mention an effective political means for defeating brutal regimes. The intellectual and political context in which Sharp was writing was dominated by the view that the states and the military not people and nonviolent methods were the source of ‘real’ power. Even now, the practitioners of civil resistance face the same skepticism with dire consequences- it was, for example, an ill-informed perception that the Syrian nonviolent resistance was too weak to challenge the Assad regime that led to its hijacking by the armed insurgency.

The authors move the intellectual conversation beyond the question of whether civil resistance can be effective against authoritarianism by focusing on how deeply civil resistance transforms the societies. By itself, this intellectual shift is a positive development and a sign of progress in understanding civil resistance and acknowledging its prowess. But this is hardly recognized in the article, which lacks a historical perspective on the development of the field.

2. The authors give way too much credit to the role of external forces or a foreign agency in influencing and determining trajectories of indigenous nonviolent struggles. In practice, when people wage nonviolent resistance they tend not to differentiate between any of the two exogenous models – ‘principled’- Gandhian and ‘instrumental’ – Sharpian as described by Chabot and Sharifi. People follow what they feel is the most appropriate and suitable means given prevailing adversarial conditions and devise their nonviolent strategies and tactics accordingly. The overemphasis on external forces that seemingly imprint either Gandhian or Sharpian philosophies into an indigenous struggle takes away agency from the ordinary people. And this, in turn, contradicts the reality on the ground where genuinely grassroots and voluntary mobilization of millions of Iranians and Egyptians – described in the article- challenged oppressive regimes and did that despite rather than because of the external actors.

3. In practical, struggle-related, terms, Chabot and Sharifi link the Gandhian ethical approach with long-term organizing based on a constructive program of building alternative institutions. The Sharpian “instrumental” approach is associated with short-term planning and execution of direct nonviolent actions. Historically, no successful nonviolent struggle relied merely on direct actions or, alternatively, limited itself to alternative institutions/constructive programs. For example, all nonviolent resistance campaigns and struggles between the 18th and 20th centuries, described in my edited volume Recovering Nonviolent History, which were waged under different geographies, in different cultural settings and historical periods, and against different regime types, were driven both by direct nonviolent actions as well as constructive methods of alternative institution-building. In other words, it is not beween Gandhian or Sharpian resistance that people choose but rather how indigenous groups deploy strategically a rich repertoire of nonviolent methods to wrest control away from the entrenched elites while ingraining political power in the population.

4. The authors blame nonviolent activists in Iran and Egypt for promoting a neo-liberal capitalist agenda and for having failed to address the root causes of structural violence. This criticism displays a degree of shortsightedness, to say the least. Gandhi’s India with its poverty, inequality and everyday violence had never seen the egalitarian and violence-free ideal, or perhaps utopia, that Chabot and Sharifi fault other civil resistance struggles for failing to advance. At the same time it is disingenuous to criticize nonviolent movements in Egypt and Iran for not reaching such goals that eluded even Gandhi and not recognizing and assessing the strategic gains made by civil resisters in both countries. Achieving the political liberation that both Egyptian and Iranian movements aimed for must be applauded rather than criticized for some unspecified nefarious neo-liberal goals. In fact, political liberation is the first sine-qua-non step to advance, longer-term, and arguably the more elusive goal of a violence-free society.

The Iranian Green movement that seemingly failed to reach its immediate objective of nullifying fraudulent presidential elections in 2009 has in fact had an enduring impact and created a legacy that four years later deterred hardliners and conservatives from rigging yet another presidential election, which ensured the victory of the moderate candidate Hassan Rouhani. This bodes well for the likelihood of easing international sanctions that are – next to the regime’s reactionary policies – the main culprit behind economic deprivation and structural violence in Iran for which the authors, paradoxically, blame the Green movement and its alleged ‘Sharpian’ leaning.

The 2011 Egyptian revolution criticized by the authors on the grounds that it was not Gandhian enough awakened politically millions of Egyptians and reclaimed for citizens a political space captured by Mubarak and its repressive regime. It was because of this revolution – criticized by Chabot and Sharifi for its supposedly neoliberal agenda – that the Egyptians remained nonviolently rebellious and pushed back the authoritarianism of the Supreme Council of Armed Forces and, later, that of the Muslim Brotherhood (MB). Where the Egyptian rebellious communities made a strategic mistake was to ally itself with the army against MB. However, at this moment, it is way too premature to offer a sound judgment about the outcome of the still ongoing political struggle and transition in Egypt. In Poland, the effects of the nonviolent resistance and the economic and social changes that followed could only be assessed with some degree of accuracy 10-15 years after the 1989 transition. In contrast to Poland, however, Egyptians still need to complete their political liberation – via both direct actions as well as constructive mobilization in the form of self-governed professional syndicates, workers’ councils, civic associations, autonomous universities, students’ unions, and independent social media. The struggle with socio-economic inequalities, illiteracy or poverty can be part of the renewed quest for political liberation but without that liberation little progress is possible.

Recent Comments